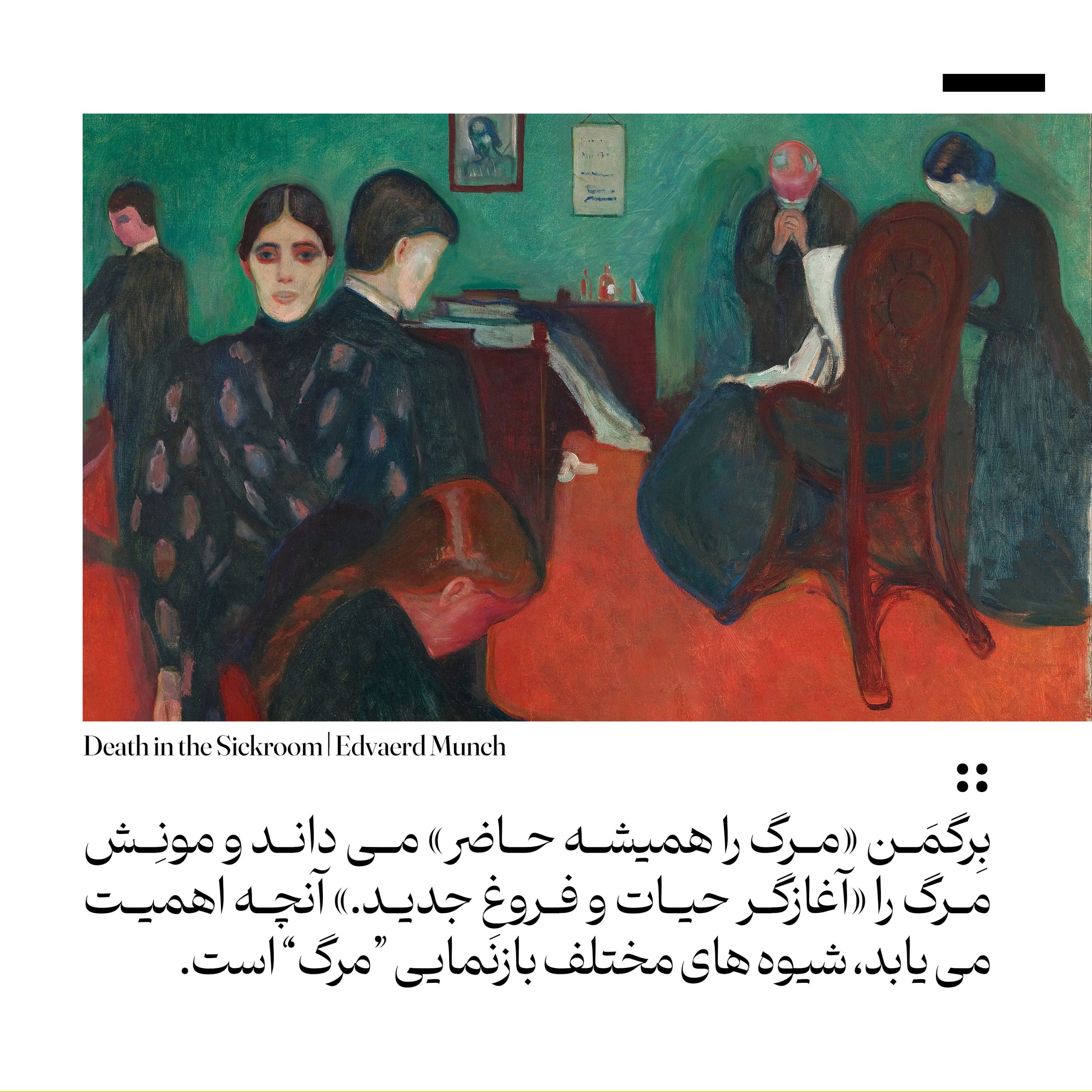

اینگمار برگمن و ادوار مونش

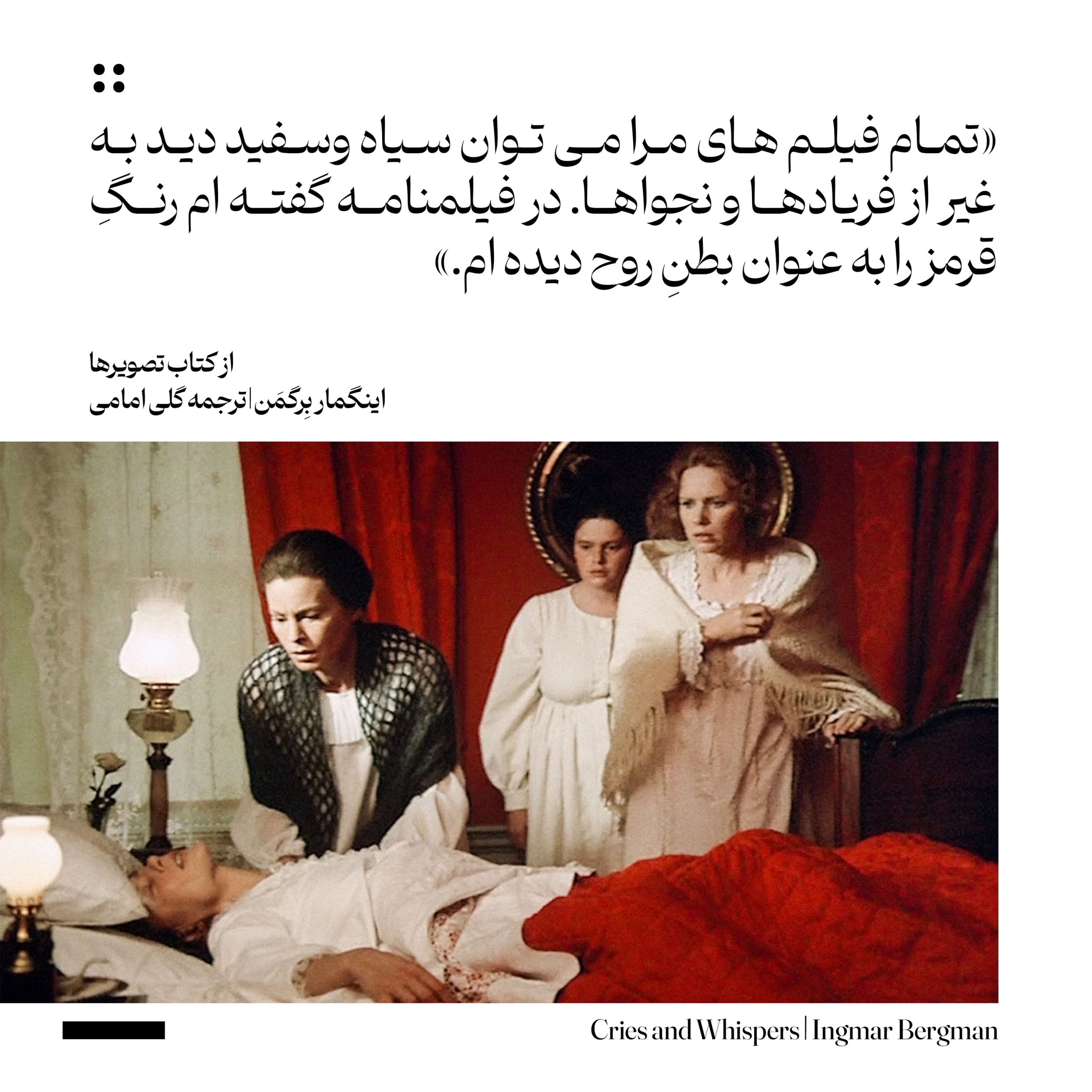

در مناسباتی بیناتصویری نقاشی های مونش و تصاویر سینمای برگمن، بازنمایی ازمرگ به مثابه بازنمایی انسان است که زیستن را در فریادها و بی قراری هایبیمار و همچنین مرگ، جستجو می کند. مونش درباره ی تجربه مرگ می گوید: «نمیخواهم ناآگاه یا بی هیچ آگاهی ای بمیرم. می خواهم این تجربه ی زیسته ینهایی را از سر بگذرانم» مرگ اندیشی که در تصاویر هر دو با ریشه های متفاوت(یکی در مشاهدات کودکی و دیگری با تجربه ی مرگ نزدیکان) اتفاق می افتد،بستری می سازد که دو نوع شیوه ی بازنمایی مرگ را مشاهده کنیم. بازنمایی ایکه بعضاً دارای شباهت می شود اما هرکدام مدیوم اختصاصی خود را به بیانیبرای بازنمایی مرگ تبدیل کرده اند. ادوارد مونش، تابلوی نقاشی را تبدیل بهصحنه ی تأتر یا فیلم می کند و در جزئی ترین حالت ها، شخصیت هایش را میزانسن می کند و اینگمار برگمن نیز. نقاشی هایی سینمایی خلق می کند که از آنها به عنوان آیکونیک ترین تصاویر سینمایی یاد می شود. برگمن در اتوبیوگرافی خود به نام فانوس خیال درباره فانی و الکساندر چنین می نویسد: «تفاوت گذاشتن میان آنچه در تخیلم می گذشت و آنچه واقعیت داشت، برایم دشوار بود. اگر سعی می کردم احتمالا می توانستم واقعیت را واقعی کنم، ولی از آن طرف مثلا، همیشه ارواح و تصویرهایی وجود داشتند.قرار بود با آنها چه کنم؟ و افسانه ها واقعیت داشتند یا نه؟

In accordance with the inter-image paintings of Munches and Bergman’s cinema images, it is a representation that searches for life in the screams and cries of the sick, as well as death. Munch says about the experience of death: “I don’t want to die ignorant or without any knowledge.” » Both images have different origins (one in childhood observations and the other in the experience of the death of loved ones). A representation that sometimes has similarities, but each of them has turned the specific medium into an expression for the representation of death. Edvard Munch transforms a painting into a theater or film scene, and in the most extreme cases, it’s not Bergman’spainting. He creates cinematic paintings that are known as the mosticonic cinematic images. Bergman writes in his autobiography Fanous Khayal about Fanny and Alexander Chenin: “It was for me to distinguish between what was happening in my imagination and what was in reality.” If I try, I might make it real, but on the other hand, there are always ghosts and images. What was I going to do with them? And legends exist or not?

این جلسه همزمان با روز سینما، 21 شهریورماه ساعت 18 در فرهنگسرای قاصدک برگزار می شود.

Sweden’s internationally best known ’visual artist’, Ingmar Bergman, did not express much interest in what we usually mean by visual art. Besides theatre and film, his own artistic fields, it was music that to him reigned supreme among the muses. Film, he has said, is above all rhythm. And film and music ”both affect our emotions directly, not via the intellect” (Bergman 1960: xvii-xviii). Bergman’s seeming disinterest in visual art, the term here used in a narrow sense as referring to immobile art, may seem corroborated by his stagings. In his three productions of Hedda Gabler he disregarded Ibsen’s stage direction concerning the painting of General Gabler to be seen – like an altar piece – in Hedda’s private inner room. In his performance of O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night he ignored the picture of Shakespeare hanging above the bookcase in the Tyrone sitting room. And in his four stagings of The Ghost Sonata he refrained from Arnold Böcklin’s painting The Isle of the Dead (1880) which according to the author, Strindberg, should be projected at the end of the play. In the last case he gave two reasons for the omittance. On the one hand people are no longer familiar with this painting, on the other he himself found it ”an awful piece of art”. But he added that as a child he was very fond of the painting, a big reproduction of which was hanging in his parental home (Törnqvist 1973: 226). It would be rash to conclude from this that Bergman as a director was indifferent to visual art.[1] When interviewed in 1968, he referred to the sculpture of Thalia in the Malmö City Theatre, where he had been working the decade before, as follows: “She’s wonderful – a huge, solid female of magnificent proportions She’s indomitable, free; her whole face is one tremendous laugh. That’s how I see theatre at its best, at its most genuine” (Björkman et al. 116). When commenting on his work as a filmmaker, he chose to compare himself to those who rebuilt the cathedral of Chartres when it had burned to the ground. “Regardless of whether I am a believer or not,” he said, “I would play my part in the collective building of the cathedral” (Bergman 1960: xxii). In a program note for his film The Seventh Seal, Bergman similarly declared: “My intention has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter, with the same objective interest, with the same tenderness and joy” (Steene 1972:70-71). Making a film or staging a play is comparable to building a cathedral in the sense that all these activities depend on team work. The difference is that the medieval artists who built the cathedral of Chartres were anonymous and did their job “to the glory of God”, whereas the leader of the team today – the architect, the director – glorifies himself by signing his work. What strikes one is that Bergman in all these cases when describing his work as a director refers to works of visual art. Hardly a sign of indifference.